Excerpts from books mentioning the song Hog-Eye Man and variations, in its original unexpurgated form. For my discussion of this song, see my blog post: She Wants the Hog-Eye Man (Sept 2024).

I have included the full text (but not musical notation, sorry) of the relevant pages from each book. The original scanned pages (extracted from the Internet Archive editions) are at the end of each section.

– Andrew Plotkin, Sept 2024

Roll Me in Your Arms: “Unprintable” Ozark Folksongs and Folklore

Volume I: Folksongs and Music

Vance Randolph

(Introduction and annotations by Gershon Legman)

University of Arkansas Press, 1992

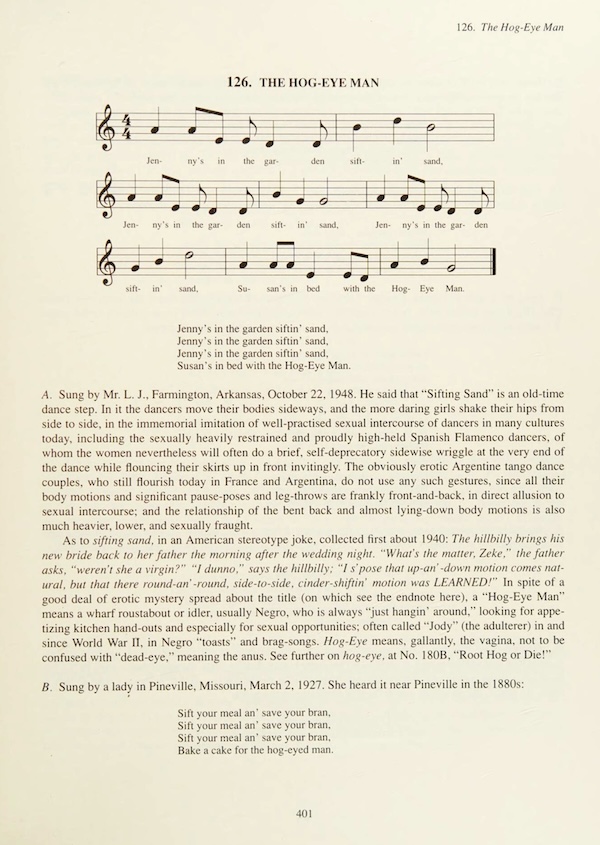

126. The Hog-Eye Man

A. Sung by Mr. L. J., Farmington, Arkansas, October 22, 1948. He said that “Sifting Sand” is an old-time dance step. In it the dancers move their bodies sideways, and the more daring girls shake their hips from side to side, in the immemorial imitation of well-practised sexual intercourse of dancers in many cultures today, including the sexually heavily restrained and proudly high-held Spanish Flamenco dancers, of whom the women nevertheless will often do a brief, self-deprecatory sidewise wriggle at the very end of the dance while flouncing their skirts up in front invitingly. The obviously erotic Argentine tango dance couples, who still flourish today in France and Argentina, do not use any such gestures, since all their body motions and significant pause-poses and leg-throws are frankly front-and-back, in direct allusion to sexual intercourse; and the relationship of the bent back and almost lying-down body motions is also much heavier, lower, and sexually fraught.

As to sifting sand, in an American stereotype joke, collected first about 1940: The hillbilly brings his new bride back to her father the morning after the wedding night. “What’s the matter, Zeke,” the father asks, “weren’t she a virgin?” “I dunno,” says the hillbilly; “I s’pose that up-an’-down motion comes natural, but that there round-an’-round, side-to-side, cinder-shiftin’ motion was LEARNED!” In spite of a good deal of erotic mystery spread about the title (on which see the endnote here), a “Hog-Eye Man” means a wharf roustabout or idler, usually Negro, who is always “just hangin’ around,” looking for appetizing kitchen hand-outs and especially for sexual opportunities; often called “Jody” (the adulterer) in and since World War II, in Negro “toasts” and brag-songs. Hog-Eye means, gallantly, the vagina, not to be confused with “dead-eye,” meaning the anus. See further on hog-eye, at No. 180B, “Root Hog or Die!”

B. Sung by a lady in Pineville, Missouri, March 2, 1927. She heard it near Pineville in the 1880s:

C. From Mr. W. B., Harrison, Arkansas, April 16, 1949. “A dirty dance song,” as he described it. Hockey, excrement. The piece of cock the singer is searching for is the vagina, not penis.

D. Text from Mr. C. P., Harrison, Arkansas, July 7, 1949. Heard near Little Rock, Arkansas, in the 1920s. In line 3, sift your meal, on coital hip-motions, as “sifting sand” in other versions:

E. Sung by a lady in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, September 14, 1949. She heard the song near Ponca City, Oklahoma, before 1918. In 1:3, hog-eye meat, vagina; 1:4, ’tater, sweet potato, allusively the penis; 2:1, sass, sassafrass, presumably aphrodisiacal; 3:4, duckin’s, blue jeans, work pants:

F. An evidently related song, known to the general American population (but collected in the quasi-Southern enclave of southern New Jersey, from a carpenter at Somerville, 1943), also sung in England:

G. Captain Stan Hugill’s “Unprintable” manuscript supplement of the unexpurgated versions of sea-chanteys he was not permitted to print in all his other books, Sailing Ship Shanties (manuscript 1956), has several of these girl-in-the-garden stanzas floating into various texts, as of “Johnny, Come Down to Hilo.” In line 2, dillywhacker, earlier British tarriwagger, the penis:

See further on this, in its abbreviated “polite” form, Brown, vol. III: p. 261, also in “The Hog-Eye Man” itself, where it is Jinny who is in the garden “a-pickin’ peas, An’ the hair of her snatch hangin’ down to her knees.” This last trait is taken from the famous pro-woman British “The Hair of Her Dicky-Dido” song, to the fine rising tune of the Welsh anthem “The Ash Grove.” Here is the rest of Hugill’s “Hog-Eye Man,” which is sung to its own tune, given with various absurdly “camouflaged” texts in his Shanties from the Seven Seas (1961) pp. 268-72, and to that of “Johnny, Come Down to Hilo,” also heavily expurgated at pp. 266-67. In 3:2, hard-on, erection; 4:2, dusters, red naval flags, metaphorically the testicles; tattoo, to drumbeat.

H. Randolph notes that Sandburg, American Songbag (1927) pp. 380 and 410-11, has several related texts. See also Sharp, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians (1932) vol. II: p. 360. Joanna Colcord, Songs of American Sailormen, 1938, p. 104 (whose text is reprinted in Botkin, Treasury, 1944, p. 836), says that “none of its versions can be printed in anything like their entirety... Terry hints at hidden obscenity in the name itself.” See Richard R. Terry, The Shanty Book, London (1921). Likewise, Bayard, Hill Country Tunes (1944) p. 75, observing that in Pennsylvania the title of the fiddle tune “Hog Eye” has “an indecent meaning.” Bayard prints one stanza:

McAtee, Rural Dialect of Grant County, Indiana, Supplement 1 (1942) p. 7, defines pig’s eye as a “euphemistic name for the very prevalent symbol for the female pudendum, an upright diamond with a longitudinal slit in the middle.” Compare the “Hog-Eye Town” piece reported by Irene Carlisle, Fifty Ballads and Songs from Northwest Arkansas, M.A. thesis, University of Arkansas (1952) pp. 137-139, referring to a village called “Hogeye,” near Farmington, Arkansas. The town of Nevada, Missouri, was known as Hog-Eye before its incorporation in 1855; Professor R. L. Ramsay, Our Storehouse of Missouri Place-Names (Columbia, Missouri, 1952) p. 111, says that “apparently the term hog-eye once signified in Missouri a small compact place sunk in a hollow.” Not very flattering for the vagina.

In addition, there is the matter of the “Row the boat ashore” chorus to the sea-chantey form, as quoted in version G above. In his excellent tracing note on this, in Brown, vol. III: p. 224, Dr. Belden points out that inland singers, who sometimes even slur it into the nonsensical Rodybodysho, have “lost all consciousness of the sea” in using it in bucolic songs. This is certainly the case with the interesting text of “Careless Love” (“Tell Your Mammy”), collected by Herbert Halpert, and given here at No. 237, among the songs collected without tunes, where the “Hog Eye Man” chorus is most inappropriately mixed in.

Blow the Candle Out: “Unprintable” Ozark Folksongs and Folklore

Volume II: Folk Rhymes and Other Lore

Vance Randolph

(Introduction and annotations by Gershon Legman)

University of Arkansas Press, 1992

237. Careless Love

[...]

C. In another strain, recovered only once, by Herbert Halpert in New Egypt, New Jersey, August 1939 (informant C. G.), the “Row the boat ashore” chorus of “The Hog-Eye Man,” No. 126 above, is used. The opening reference to fifteen cents is obscure: either the boy or the girl involved in this colloquy has paid the other that ludicrously small sum, evidently for some sexual “show-and-tell” display or permission, which is now being refused out of fear of pregnancy (the “big bell-y” of stanza 2:2).

In 3:3, musharoon, a conscious allusion to erotic symbolism in dreams: the mushroom and fast-growing springtime wild asparagus are among the most common rural folk symbols for the erect penis. This is taken cognizance of in the scientific nomenclature of mycology: one of the deadliest mushrooms is called Amanita Phalloïdes; another is commonly known as Dog’s Prick, both because of their shape; and compare the common Phallus Impudicus, or “shameless penis,” the large arum or “Cuckoo Pintle,” this being another old term for the penis, and therefore expurgatorily abbreviated to “cuckoo pint,” “wake-Robin,” or “Jack-in-the-pulpit,” unless the Robin and Jack (the modern “john”), also imply the same. W. L. McAtee has published an entire monograph, Nomina Abitera (Privately Printed, 1945), on this type of erotic and erotico-scientific nomenclature. In the chorus: hog’s-eye and pig’s eye, the vagina, or its split “upright diamond” symbol. (Not to be confused with the nautical slang, dead-eye, the anus, or a Turk’s-head knot in rope.) “Hog’s-eye man,” an inveterate wencher or “cunt-hound,” a man obsessed with women and sex, also called “Jody.” See texts at No. 126 above. The first and last stanzas here are in the metrical pattern of “Yankee Doodle,” No. 209:

The Hog-Eye Man.

This shanty dates from 1849-50. At that time gold was found in California. There was no road across the continent, and all who rushed to the goldfields (with few exceptions) went in sailing-ships round the Horn, San Francisco being the port they made for. This influx of people and increase of trade brought railway building to the front; most of the “navvies” were negroes. But until the roads were made there was a great business carried on by water, the chief vehicles being barges, called “hog-eyes.” The derivation of the name is unknown to me. The sailor in a new trade was bound to have a new shanty, and this song was the result:

and so on.

As nautical readers know, much of this shanty is unprintable; but it was so very much in evidence in the days of shanties that a collection would be imperfect without it.

And now we come to a shanty usually spoken of in hushed tones by collectors—I don’t know why; many other shanties were just as obscene, and even worse! This is the ‘notorious’ Hog-eye Man which is supposed to rank with Abel Brown the Sailor in infamy. Terry devotes several paragraphs trying to explain why it wasn’t decent, and what the hidden meaning of the term ‘Hog-eye’ was in the minds of dirty old sailors, but with all his verbosity and hinting he doesn’t explain a thing. As a matter of fact Whall, ‘Seaman of the Old School’, gives an explanation of the word ‘Hog-eye’ without any obscene entanglements. He plainly states that it was a type of barge invented for the newly formed overland trade which used the canals and rivers of America at the time of the Gold Rush (1850 onwards). A ‘Ditch-Hog’ was a sarcastic phrase used by American deep-watermen to denote sailors of inland waterways such as the Mississippi and Missouri as opposed to foreign-going Johns. I rather think Terry got his words mixed—he was thinking of ‘Dead-eye’ and not ‘Hog-eye’, the former having both a nautical and an obscene significance. Nevertheless the solo parts were indecent, and a large amount of camouflaging was necessary before this song could be made public.

Davis & Tozer give it as a pumping song with a shortened chorus:

Normally however it was used at the capstan.

THE HOG-EYE MAN

Alternative Titles, The Hogs-eye Man, The Ox-eye Man, The Hawks Eye Man

Sometimes stanzas from A-rovin’ would be used. The tune and the theme of this shanty varies but little, but there are several forms of the chorus:

Chorus variants—

In the Journal of the Folk Song Society there are two choruses sung by Mr. Bolton of Southport to Miss Gilchrist (1906):

Both Johnny, Come Down to Hilo and this shanty were more popular when there was a Negro shantyman aboard, since both contained when sung properly, many ‘hitches’ and wild yelps. This shanty probably started life as a railroad work-song (many railroad navvies were Negroes), then taken over by the ‘river boys’ and finally, by way of the cotton hoosiers of the Gulf Ports, passed into the hands of deep-water sailormen.

A version of it when a Negro work-song I came across in N. I. White’s American Negro Folk-Songs (page 454). He, in turn, had taken it from a book called Twelve Years a Slave (New York, 1855):

(By permission, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.)

More recently I found a Negro ‘Hog-eye’ work-song in The American Songbag (Sandburg, page 380). The collector writes:

... A lusty and lustful song, developed by the Negroes of South Carolina, who had it from sailors originally is Hog-eye. In theme it is primitive, anatomical, fierce of breath, aboriginal rather than original. One lone verse passing any censor is presented. ...